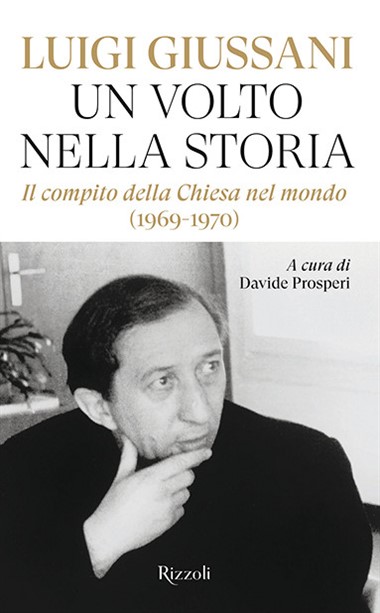

This volume collects eleven lessons given by Luigi Giussani for the first edition of the “School of Communion” at the Péguy Center, between March 1969 and June 1970. The monthly lessons were addressed to adults who, after the crisis of 1968, wanted to continue and renew the Christian experience they had begun at school.

The text expresses Fr. Giussani’s conception of Christianity and its relevance for the formation of a mature human personality, capable of new judgment and action.

The chapters of the book—the titles are the original titles of the lessons, with slight shortenings in some cases—are connected to each other progressively—each chapter referring to and developing the previous one—and thematically. Thus, Chapter Two takes up and deepens Chapter One; Chapter Three concludes the first part of the discourse and provides the starting point for it to progress; the theme of Chapter Four is considered the starting point of the entire Christian discourse, the subject of Chapter Five is the methodological keystone, and the subject of Chapter Six is its ethical and cultural determinant. From Chapter Seven onwards, the characteristics of Christians in their way of living their relationship with life and the world according to the Christian faith are considered.

Chapter One (“The Church and the World”), attempting to define the connection between the objectification of Christian communion (Church) and the sphere of human life (world), consists of two principles and two methodological guidelines. The first principle concerns the purpose of Christianity (that is, of Christ and the Church), which is clearly identified as the religious education of humanity. The second principle concerns the task of Christians, who collaborate in the concrete resolution of personal and social problems according to two coordinates: their historical-temporal location (history, time, evolution) and human freedom (which also includes genius, generosity, intelligence, and will). These two principles are implemented through two corresponding methodological laws: Christian communion, the Church, as a method for communicating and participating in the “Christian fact,” and incarnation, as affecting human problems through one’s own humanity. The final Nota-Bene emphasizes the inseparability of the four factors and the tension they impose on life.

These themes are taken up and explored in greater depth in Chapter Two (“The Mission”), in meditating on the word “mission,” considered central to the concept of Christian personality. After retracing the figure of Christ in the Gospels as the one who was “sent” and after indicating the meaning of Christian life in participation in His mission, emphasis is placed on mission and poverty as being synonymous—and thus on detachment from oneself and one’s possessions—before moving on to the three factors of mission. The first concerns the subject of the mission, which is the establishment—through grace, gift, and historical participation in the body of Christ—of the Christian personality, as what comes before every action and as space for communion. The second factor is the content of the mission—announcing the Father’s good plan, in the paradox of the cross and in the certainty of the resurrection, so that God may be all and in all. The third is the condition of the mission—being fully involved with the human condition and with the urgencies, needs, and problems being raised. The chapter ends with a reminder of the urgency of having a presence, a face, in the world, as we strive to improve it and we are confronted with inevitable hostilities.

The development and conclusion of the first two chapters can be found in Chapter Three (“Veritatem Facientes in Caritate”), which examines the theoretical and practical cornerstones of the Christian conception. The first cornerstone—the foundation of Christian hope, as human hope, is the mystery of Christ, made present in the Church. And hence, as the second cornerstone, in order to contribute to change and improve the world, the need to build the Church, in the human condition and in the situations in which people find themselves, starting with the closest ones. Third—communicating to the world the change that takes place within the Christian community, avoiding any dualism, since the world is within the Church and the Church is the horizon of change in the world. In this regard, and fourthly, belonging to the Christian community is not defined arbitrarily but is open to all those who recognize and accept the Christian announcement. Finally, the fifth cornerstone is the need for a Christian community to bring about the tangible change brought by Christ in relationships and in the events of life, that is, “miracles” that realize the truth in charity.

Chapter Four (“Comprehensive Christ, Our Hope”) contains the book’s main thesis, Christ, our hope, introduced as the first sentence of a page that will be filled in the following chapters. First of all, we note the radical nature of this statement, which is normally accepted because of its comprehensiveness—for Christians, hope founded in Christ has value in this very life, involving the totality of the human personality and life. This changes the conception and perception of the future, which must not be separated from the present, but is its realization, that is, it is considered the fulfillment of a salvation that is already present. The continuity between the present and the future is the “big news” that serves as a premise for three main points on hope, as follows: a) hope permeates all of history—Christ as comprehensive hope concerns life in all its aspects, in the present and in the future; b) this hope changes the way we see and analyze life, both personal and social; c) Christian hope acts on the person, because through this hope the problems of the world are solved. The importance of the phenomenon of the person is emphasized by the value of prayer and friendship, referred to at the end of the chapter.

The discussion on hope finds the fundamental methodological element in time, which is the subject of Chapter Five (“Christ and Time”). After recovering the very close connection between Christian hope and the salvation of man, three main points are developed, divided into internal paragraphs.

First, human time is implicated in Christ’s salvation as a dynamic that stimulates human freedom, understood as a striving for the complete fulfillment of the human being—and therefore oriented toward the future—but also as a conditioning factor along the journey, with regard to the choices that can be made.

The second point deals with “God’s plan” in relation to the existence of the individual human being and “God’s will” as a historical event, which brings life into the “plan”—the covenant between God and the Jewish people in the Old Testament, the new creature who is born through baptism in Christianity—.

The third point is devoted to anthropological consequences: first, faith, presented as what qualifies the figure of the new human being; second, patience, as the attitude that faith prompts in human beings in their relationship with things and with themselves. Two fundamental factors of patience are pointed out: the awareness of the good purpose of all things and the energy with which things can be possessed.

After Chapter Five, we begin to examine the face of Christians in the world and, therefore, the value and nature of building the Church.

A first element of this physiognomy is the new judgment generated by faith, the new mentality that springs from Christian conversion. The theme is introduced in Chapter Six (“The Final Judgment on the World”) and taken up again in Chapter Ten, with regard to sharing in human need.

As a prerequisite for the ability to judge reality, reference is made to the God of the Old Testament, who manifests himself as Lord of history through knowledge and judgment. Christ represents the fulfillment of this prophetically stated view of things, as justice—the overcoming of the old law—and judgment—the meaning of human existence and history. In His controversy with the world, as the Gospels attest, Christ introduces a new criterion for judging reality. He is the touchstone for defining the value of human action in history and finds in the Christian community, the Church, the place where He can demonstrate His victory. So, for Christians, faith is first and foremost knowledge of the synthetic criterion for judging reality, and Christian communion is the genesis of new judgment and, therefore, new action.

A brief summary of the path taken opens Chapter Seven (“Poverty, the Face of Christians throughout History”), dedicated to the first aspect of Christians in the world, poverty of spirit. In the dialectic of the Christian vocation between “already” and “not yet,” poverty is the root of an intelligent and true possession of things and goods, well described by Saint Paul in his Second Letter to the Corinthians. The poor live in peace and are sustained by boldness, pure and sincere in their intentions, capable of true charity and joy, always vigilant and attentive, even if they are pilgrims and strangers on earth.

Poverty is thus the first category in the building of the Church. This is followed, as the second category, by a commitment to liberation from evil, the subject of Chapter Eight (“Liberation from Evil”).

First introduced by looking at the problem of evil in relation to human freedom and at God’s plan of salvation, liberation from evil finds its roots in God’s gratuitous act of freedom towards man, in the paradox of the righteous sufferer, and in the definitive victory through the death and resurrection of Christ. To man, this death and resurrection are communicated by the Spirit, as a gift—kerygma and sacraments—that puts down in him the root of liberation and a new heart.

In all this lies the Christian ideal—in the true and permanent possession of things. This “fragile and precarious” subject, dealt with in Chapter Nine (“Possessing Reality in the Risen Christ”), is considered in close relation to the search for the fullness of one’s being and the maturity of a Christian’s conscience and feelings. The possession of things and of oneself had been prophetically announced in the Old Testament, in the ideal of new heavens, of an era of fertility and wealth, of a renewal of the heart that would lead to a new earth, where peace would reign. Through Christ, this new possession was made possible; in recognizing this lies the profound value of “virginity” as experience of something new, in a human sense, capable of living in peace and communion and bearing witness to it, as was the case with the first martyrs of Christianity.

Chapter Ten takes up the theme of judgment (“New Judgment and Theory”) and the initial theme of the course—the relationship between the life of communion and worldly reality, or, more precisely, the connection between Christian faith and human need. Reflections on the issues of sharing, social justice, and the effectiveness of actions to improve human conditions are particularly important both from a historical perspective—the emergence of an original position after 1968—and in terms of the concept of Christian commitment in the world. In terms of sharing needs and the effectiveness of social action, particular emphasis is placed on the importance of truly understanding concrete situations and acting authentically.

Chapter Eleven (“Work and Mission as Conversion”) concludes these meditations. By reiterating the theme discussed—the “salvation of the world,” the hope placed in Christ for one’s own salvation, for the salvation of others, and of the world—this chapter retraces the words of the journey taken—salvation, hope, patience, poverty of spirit, Christian communion, building up the Church. Two mistakes to be avoided are pointed out—a secularized conception of behavior and a moralistic-cultic conception of Christianity—and we are urged to an intense and total missionary commitment, in the sign of an indomitable passion for Christ, for the Church, and for the salvation of the world.